Wealth and Riches? What’s the Difference?

Last Friday, I explored the implications of Pareto for the local economy. This principle suggests inequalities between neighbourhoods are inevitable. What are the implications for a thriving marketplace in every neighbourhood? In this post, I want to question this from a different angle by exploring differences between wealth and riches.

[amazon_link asins=’1612680194′ template=’ProductAd’ store=’markettogether’ marketplace=’UK’ link_id=’3c36efca-0035-11e8-8854-ab6da33d912b’]To do this I shall review the book “Rich Dad Poor Dad: What the rich teach their kids about money – that the poor and middle class do not!” by Robert T Kiyosaki. This week I shall explore some positive insights from the book. Next week I’ll explain where I disagree with it.The author tells the story of what he learned about wealth from his own father and the father of a friend. The story is well-told and I have found since reading it, I hear what the wealthy say in a different way. This worldview is new to me although not entirely unfamiliar.

Here are two important insights from the book; I encourage you to read it because there are many more.

The Importance of Learning

One welcome and not unfamiliar insight is learning is important. The author suggests working to learn is far more important than working to earn. The wealthy understand learning about how the world actually operates is important. The more they know, the more likely they are to recognise financial opportunities when they encounter them. And of course they know what to do to invest in them.

This immediately resonates with the observation marketing is essentially educational. Most business people seek investment in their businesses, most often through their customers. This may be particularly true for B2B customers, although I can think of non-business transactions that are also investments.

The point is most of us do not learn how money works at school or in our families. Even accountants don’t understand it the same way as the wealthy do. Once you understand the strategies wealthy people use, you can hear them talking about them in radio and TV interviews.

They see themselves as free spirits who do not subscribe to the rules the poor and middle classes follow. There is a lot in this and I can empathise because I made a similar decision to abandon the rat race 30 years ago when I left my work as a research scientist for community development.

The problem for people who make similar decisions to mine is we do not usually buy into building our wealth. Most are altruistic and then find later they have to abandon community development and opt back into the mainstream to fund their family.

There is a good deal of common ground between the radicals who opt for alternative employment and the wealthy who opt to build financial independence. I’ll highlight where we part company in my next post.

Wealth or Riches?

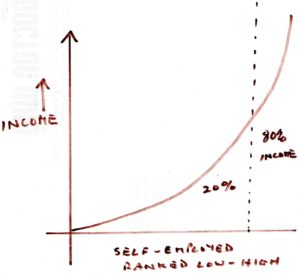

We all know stories of people who win the lottery and in a few years have nothing left. They were rich but not wealthy. The wealthy person may not have a lot of money in their current account but can pay their bills. The rich pay their bills but every time they do so, make themselves poorer.

Of course, the wealthy do this by building their investment portfolio. They understand and trade in things like shares, real estate or intellectual property. The wealthy spend time building and maintaining that portfolio. They may not have a lot of ready cash but once their income from investments pays their bills, they are financially independent and therefore wealthy.

This is an important insight because it gives the lie to those who promise massive riches through some marketing scheme. It is not the volume of income you receive from work so much as what you do with it. The people who make large sums of money from their business may be rich but are they wealthy? What would happen if their business failed?

But note it also means wise investment of funds means you actually don’t need to turn over vast sums of money.

This is what I meant last week when I suggested perhaps we’re asking the wrong question when we discuss inequality between neighbourhoods. Of course some neighbourhoods will do very well and others less well. But investment in our neighbourhoods is also important.

Wealth in the Local Economy

But how do we build investments for our neighbourhoods? Do we rely on wealthy people to increase their own wealth and use it to invest locally? Or do we create organisations that build assets, they can invest in their neighbourhood?

The last was the original purpose of development trusts, now often called social enterprises. Their problem is they are not usually run by entrepreneurs and so fall back on what they know, namely dependence on grants. When they own assets, it is usually a building in which they’re based. Usually that building is a liability.

This suggests business people are crucial to local regeneration. It is a pity they have been and continue to be marginalised. Next time I’ll explain why I think that is, when I look at where I part company from Kiyosaki.

So, this is my question: is it possible to build an asset base in support of our neighbourhoods and the local economy? If so, how?