Personal Branding

I’m not sure I know what to make of Personal Branding. We’re all familiar with branded products and retailers. If we think about it, we can see their point. A familiar brand is trusted, memorable. You pay your money and know almost exactly what you’ll get in return.

But personal branding? I am not a product or a business of any description. Why should I be branded and what does it mean?

I’ve based the following thoughts on a new book, “Branded You: How to Stand Out in Business and Achieve Greater Profitability and Success” by Adele McLay. (The book will be published soon, follow the link and scroll down to register your interest.) The book brings together all the ideas you need to build your personal brand. It is really helpful to find them all in one place. It is an easy read and short enough to return to for deeper reflection, as you work through each part.

I’ve had the following thoughts in response to the book.

Outer Branding

Don’t make the mistake of thinking outer branding is somehow superficial. If your branding is superficial, then you haven’t done the work. Integrity is a core principle here. There needs to be coherence between you and what you sell.

Your story, your appearance, your public persona are all elements of your personal brand. These need to be consistent with each other and coherent with your offer and your market.

The challenge is to make the right choices. If you help people overcome their problems through outdoor activities, do you approach your market dressed for outdoor activities or in regulation business clothes?

There is no correct answer because the question is a challenge. Your brand is to accept neither option but to seek something that works for you. Find a creative solution to build your brand.

Your Brand as a Mask

The masks in ancient Greek theatre communicated the character through sound (Latin: per sonar) Clker-Free-Vector-Images / Pixabay

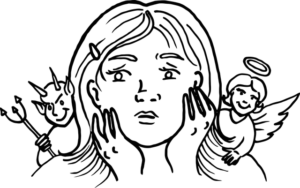

The paradox is the outer brand is a mask. But the mask you wear is you! It may be a heightened version of you but it must be genuine. The Latin word persona goes back to Greek and Roman theatre and refers to the masks Classical actors used to wear.

Their masks concealed the actor’s identity and amplified their voice. The paradox is the character depicted through the mask was always more real than the actor behind the mask. The personal brand similarly amplifies the person behind the mask but with coherence between the brand and the actor.

Inner Branding

You can see there is an inner discipline to personal branding. You need to work on congruence between how you present yourself and what you promote.

This always feels awkward to me. I am naturally disposed to being a grumpy old man. When I was a teenager, someone referred to my husky exterior. So, I’ve been a grumpy old man for many years. I am sceptical that I can present myself as relentlessly positive.

On the other hand I know I can be engaging. I can inspire people through spoken words. I speak with humour, energy and passion. And I love doing it! Is this really me? I surprise myself sometimes.

My problem is I naturally present myself in grumpy mode and can in the twinkling of an eye transform myself into my other persona. I couldn’t be energetic and engaging if it were not for my grumpy demeanour.

My problem is bringing the two together, so my brand has coherence. And the truth is, this is something everyone in business struggles with. Your natural and public dispositions need not be at odds and your brand is how you find a creative solution to presenting both.

McLay’s book describes the necessary practical approaches to working on your brand in both its outer and inner aspects. If you work through her 7-step programme, you will build a personal brand and hopefully a successful business as a result.

Outward Branding

Here is something I don’t think McLay or other writers are aware of. How does your brand reach outwards? This is not about how you appear to the world but the impact your personal brand has on the world.

We are not isolated individuals. We are all part of various communities and our brand is a measure of our influence in those communities. To some degree, my brand represents all the communities to which I belong, not just my business.

I live in a part of Sheffield that has had a poor reputation in the city for many decades. If people know I come from Pitsmoor, this could devalue my personal brand. But I want to advocate Pitsmoor as a positive place. I need to find creative ways to do that. It is perhaps not an easy call but it is something all businesses should consider.

Roots and Branches

If you have a global market, the street in which you park your business may not seem that important. You probably chose it for all sorts of reasons, not least costs. If you’re selling to someone even a few streets away, your place may seem irrelevant.

But we devalue our neighbourhoods as we leave them for town or shopping centres. Maybe businesses need to advocate their place, grow the roots that support their many branches?

When we do this, we support other businesses and grow the communities we need to support enterprise in general.

Again this type of personal branding requires time to develop ideas and grow solutions. It’s not about ramming the delights of Pitsmoor down the throats of my customers; it is being rooted in a place and committed to it. Open to ways to build sustainable community there.

Have you encountered examples of outer, inner and outward personal branding?