Pareto in the Local Economy

Last Friday, I introduced the Pareto Principle and today here are some problems it throws up. I’m not saying there’s anything wrong with the principle that 20% of inputs result in 80% of outputs. However, Pareto raises issues for regeneration of communities. So, what can we learn from Pareto in the Local Economy?

Inequality is Inevitable

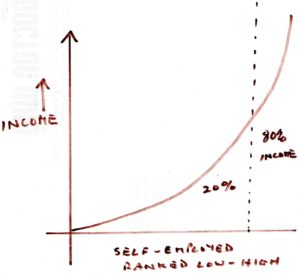

First, consider the Pareto curve. If we accept the Pareto principle, we do not need to measure everything to make predictions about the economy. If we took every self-employed person, ranked them from the lowest income to the highest, we know we would get the Pareto curve.

Twenty percent of the self-employed (the same would apply to other groups in the local economy, eg traders or businesses) would make 80% of the money generated by their businesses. Remember the curve is fractal and so 4% of the original number will make 64% of the available money. This is statistical and so the real figures will not be exactly the same but the principle will hold.

We can see there will be a long tail of low paid self-employed and most of these will sooner or later go out of business.

What Pareto tells us is inequality is a statistical inevitability. We all know most businesses do not survive and a few do very well indeed.

One feature of the modern business world is the guru, who has found success and shares their advice, often with generosity and usually offering support at a price. They have a winning formula, it works for them and they can point to others who have learned the trade at their feet.

But if everyone learns their methods and applies them we will still have the Pareto curve. Some people will do much better than everyone else.

Neighbourhood Inequality

Now, let’s consider neighbourhoods. There is a problem here because it is hard to define a neighbourhood; where does this one end and the next begin? Also, do we define neighbourhoods by area or number of businesses? By money in circulation or the wealth of the businesses based there?

Whether this is research that would be worth doing and possible to do is a matter for conjecture but we can say if it were possible to rank neighbourhoods according to their wealth, we would expect the Pareto curve.

This is intuitively true, we would expect some neighbourhoods to be far wealthier than others. City centres for example will have much more footfall than out-of-town estates.

I think we can be fairly confident this is true and inequality is inevitable between communities. Some will always do better than others. There are many complicating factors and reasons why some places fare better than others but statistically we would expect that to happen.

So, does this mean my vision of a thriving marketplace in every neighbourhood is an impossible dream? Well, it was never going to be easy. But Pareto suggests it is impossible.

But to leave it like that is to allow injustice to continue and for many that is intolerable and increasingly unsustainable for society. The evidence suggests our world is becoming more unequal and the Pareto curve tells us why, because more wealth is accumulating in fewer hands.

It may be statistically inevitable but if it is, it means so is bloody revolution. The rise of populist movements worldwide is clear evidence of malcontent, unlikely to be mollified by stories of the statistical inevitability of their misfortune.

I suspect the problem is we’re asking the wrong question. I’ll return to this issue over the next few weeks.

What alternative questions would you ask?